The Basics of ventilation.

To understand the importance of ventilation in our homes, it’s essential to grasp how moisture moves around our homes, including the roles of relative humidity (RH) and dew points.

Ventilation involves the exchange of fresh outdoor air with stale indoor air. This is particularly important when insulation is installed, as the movement of air becomes resisted.

Each section of this site offers more details, with key points intentionally repeated to strengthen comprehension.

Ventilation is covered by Part F of the UK Building Regulations.

When water vapour cools and turns back into a liquid, it’s called condensation. (steam from a hot bath cooling down on a cool surface, like a mirror, window or walls)

What is moisture, water vapour, Relative Humidity and Dew point?

Moisture is just water, but in a very small amount that you might not always see or feel.

It’s what makes the air feel damp or humid, it can make surfaces feel wet or sticky, or make materials like wood or fabric feel slightly wet or clammy. Moisture can be described as the amount of water vapour in the air.

Water vapour is just water in its gaseous state, this is why you can sometimes see your breath in cold air.

Relative humidity (RH) is a measurement of how much moisture (water vapour) is in the air compared to how much the air can hold at a given temperature. It’s expressed as a percentage. Moisture is released from the air when the air becomes saturated (full) and can no longer hold any more (think of a sponge).

This process is known as condensation, and the point at which it turns to water is known as the dew point.

Relative humidity (RH) is expressed as a percentage. If the relative humidity is 50%, it means the air is holding half the amount of moisture it could potentially hold at that temperature.

Some humid countries experience rare occurrences of RH reaching 100%. This YouTube video is quite eye-opening!

The dew point is the temperature at which air becomes saturated with moisture and starts to condense. It helps us understand humidity levels and is an important factor in how we heat and cool our homes (as well as predicting the weather!). Using a dew point calculator, we can see at what temperature with specific RH that condensation will occur.

The below videos can help with the explanations of some key points.

Videos are from the UKCM and Aereco.

What is Purge / natural ventilation?

This involves the use of openings such as windows, wall vents, and trickle vents to allow fresh air to enter and stale air to exit the building naturally. Purge ventilation is required in each habitable room and should be capable of extracting at least four air changes per hour (ACH) per room directly to the outside.

Full purge ventilation can typically be provided by opening a window and is classed as intermittent.

We also have adventitious air, which is the natural ventilation that comes into a room from outside through cracks in doors, windows, and floorboards.

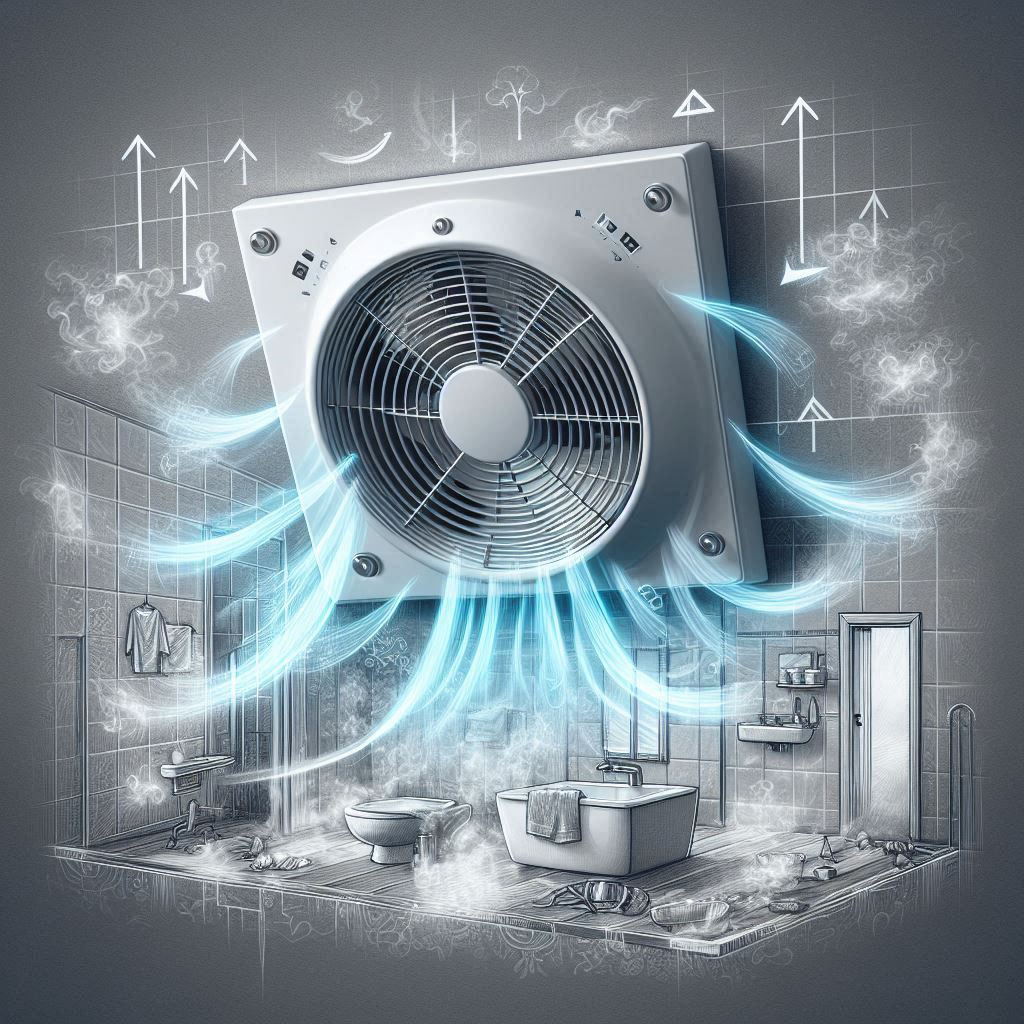

What is a Mechanical ventilation system?

The use of fans or other mechanical devices to extract stale air from the building and introduce fresh air from outside via natural ventilation. These systems may include extractor fans in bathrooms and kitchens, as well as whole-house ventilation systems. Some are always on and some are manually controlled when required.

Some whole house systems may have a purge setting.

What is controlled ventilation?

Intermittent extract ventilation (IEV) is a system where extraction is used only when needed. Typically, it is controlled by the occupier through a pull switch or automatic activation when the light is switched on. This method ensures efficient removal of indoor pollutants and moisture, maintaining better air quality without continuous operation.

Decentralized mechanical extract ventilation (dMEV) is a ventilation system designed to continuously extract stale air directly from specific rooms, such as kitchens and bathrooms, thus improving indoor air quality.

Unlike central systems, dMEV units are installed in individual rooms, providing targeted ventilation without the need for extensive ductwork.

Mechanical extract ventilation (MEV) is a ventilation system designed to continuously extract stale air from multiple areas within a home, such as kitchens, bathrooms, and utility rooms. Unlike intermittent systems, MEV operates constantly at a low rate to ensure a steady removal of indoor pollutants and moisture.

Positive input ventilation (PIV) works by drawing fresh air in through the unit that’s usually, but not always, installed in your loft. This air is then filtered and gently diffused at ceiling level, creating a positive pressure within the home that forces air pollutants out through the natural leakage gaps found in every UK property, both old and new.

Mechanical ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR), is an energy-efficient ventilation system commonly used in buildings to provide fresh air while minimizing heat loss. It’s particularly popular in modern, airtight buildings where natural ventilation may be limited.

Trickle vents are small openings integrated into window frames or walls that allow a controlled amount of fresh air to enter a building. They provide passive ventilation, helping to maintain indoor air quality without the need for active mechanical systems.

Now let’s put this together!

The ideal relative humidity (RH) for comfort typically falls between somewhere between 30-60%, depending on factors such as the season and personal health conditions, like respiratory issues.

Warm air has a greater capacity to hold moisture, but as it cools, this capacity decreases, leading to condensation.

A common example is after taking a shower, you place a damp towel on a warm radiator or in a heated room to accelerate the drying process. The warm air absorbs moisture from the towel, increasing the room humidity, however, this moisture-laden air tends to migrate to colder areas of the room or rest of the property.

When it reaches surfaces at or below its dew point—such as windows, mirrors, ceramics, behind wardrobes on external walls, or poorly insulated areas (cold bridges) condensation occurs.

This condensation can occur behind poorly installed insulation or insulation that has failed over time, which means it cannot be seen. This is called interstitial condensation.

This process then repeats, highlighting the importance of proper ventilation to prevent moisture build-up and associated issues.

So why Ventilate.

All this can lead to mould growth, odours, and damage to furniture, structures, and health.

Proper ventilation, moisture control, and regular maintenance are crucial for managing our homes.

In the UK, building regulations define different types of ventilation for this purpose.

How to control.

To control moisture and ensure comfort in our homes, designed “controllable” ventilation is crucial. It helps manage indoor humidity by helping to remove excess moisture, which prevents mould and mildew growth that can damage structures and worsen respiratory issues. Ventilation systems, like extraction fans in bathrooms, utility rooms and kitchens, are key to preventing moisture build up. Controlling the ventilation is more than just flicking a switch.

Depending on how airtight our home is, we have to think about replenishing our surrounding air that we are removing. This is done by looking at air movement around the property. You may think having trickle vents in your windows let big drafts in, but they don’t really if installed at the *right levels and fitted correctly. They come into their own when extractor fans are running in wet rooms, and the doors throughout the property have clearance at floor level to allow the movement of air.

More detailed information on heat, air, and moisture movement (HAMM) is here.

* Background ventilation should meet current regulations, 1700mm minimum from floor level and be controllable by occupants.

Improving Indoor Air Quality.

Improving Indoor Air Quality (IAQ) requires adequate ventilation to remove pollutants like volatile organic compounds (VOCs), carbon monoxide, allergens, dust, and mould spores.

Ventilation exchanges stale indoor air with fresh outdoor air, promoting a healthier environment and reducing respiratory risks.

VOCs, such as formaldehyde, benzene, and ethylene glycol, are present in many everyday products like cleaning supplies, air fresheners, cosmetics, paints, candles, and glues. We also have carbon monoxide, allergens, and dust to contend with.

Regular ventilation helps reduce these pollutants, ensuring cleaner and safer indoor air.

Modern appliances such as dishwashers, clothes dryers, and air fryers add moisture through evaporation and reduce the quality of the air, so adequate controlled ventilation helps maintain the balanced environment and can also become part of the household’s *energy efficiency plan.

*By using controlled ventilation heat loss is reduced as windows do not need to be opened especially in winter.

Installation guide.

Ventilation regulations in the UK are designed to ensure adequate air quality, prevent dampness, and maintain healthy indoor environments. The key regulations and guidance documents include the following:

Building Regulations. (Approved Document F)

This is the primary legal framework governing ventilation in buildings. It applies to new builds and significant refurbishments in England and Wales, including insulation.

The government website has a basic outline and the main points include:

Adequate Ventilation. Provision of natural ventilation (windows, trickle vents etc.) or mechanical systems (e.g., extractor fans).

Ventilation Rates. Specific airflow rates for different spaces, such as bathrooms, kitchens, and living areas.

For example:

Kitchens: 30 litres/second for a cooker hood to outside air, or 60 litres/second for other mechanical ventilation. Bathrooms: 15 litres/second for mechanical extractors. Link here.

The Clean Air Act 1993

Focuses on controlling air pollution. It applies to the design of ventilation systems to ensure they do not release pollutants into the atmosphere. Link here.

BS EN 16798-1:2019

This British Standard provides technical guidance on achieving adequate indoor air quality through design and operation. Link to BSI here.

Additional Guidelines.

CIBSE Guidelines: The Chartered Institution of Building Services Engineers provides detailed guidance on best practices for designing ventilation systems, including natural and mechanical options.

Part L of the Building Regulations: Focuses on energy efficiency. Ventilation systems must balance energy use with adequate air circulation to comply with energy-saving standards.

Damp and Mould Regulations: The last BS standard has been withdrawn, and the UK government has produced guidance.

For regulation links for social housing and landlords, go here.

Gas and open flued appliances.

If the fabric of the property is being improved and open-flued gas appliances exist, then a gas spillage test should be carried out on each appliance by a suitably competent operative.

Rules exist that give an average unimproved property a certain amount of leakiness (adventitious air) to allow open-flued appliances to operate safely.

This all depends on how much fuel burns over a period of time, for example: 7.5kw/hr, 9kw/hr, 6.9kw/hr. You will see this on the data badge of the appliance (gas rating of an appliance here.). The more fuel used, the more leakiness is needed. Multifuel appliances are treated in roughly the same way but do not come under gas safe legislations. HETAS and building regulations govern multifuel installations and ventilation.

This is the reason combustion ventilation is sometimes needed. This allows the air to be replenished (with an open flued appliance we are burning the oxygen in the room that we use to breathe)

With the introduction of insulation, extraction ventilation should be installed as part of the process, we now have a different factor to add in with gas safety. Extraction fans either pulling or pushing air (PIV) can now effect the performance of the appliance.

Open flued gas appliances should be checked to prove they are not spilling products of combustion into the property. This is verified by performing a spillage test.

Part J states. “Extract fans lower the pressure in a building, which can cause the spillage of combustion products from open-flued appliances. This can occur even if the appliance and the fan are in different rooms”.

Any funded insulation work now includes ventilation upgrades as part of the current PAS, so extract ventilation will be installed. This should have been factored in as part of any ventilation work carried out. A competent person is required to perform spillage tests.

Part B, 8(1) of the Gas Safety (Installation and Use) Regulations 1998 states that no person can make any changes to a premises that contains a gas fitting or storage vessel if the changes would compromise the safety of the fitting or vessel.

This basically means if the fabric of the building (walls, floors, roofs) are being insulated then appliances need to be checked by a suitably competent and qualified person.

Regulations.

Part F of the UK Building Regulations, sets out requirements for ventilation in buildings to ensure adequate indoor air quality and prevent issues such as condensation, mould growth, and the build-up of pollutants.